Gaining

A Competitive Advantage With

Lean

and Six Sigma Philosophies and Tools

Kenneth A. Polcyn,

Ph.D.

Senior Consultant

© 2006 Deva Industries, Inc.

And

Steven S. Engelman

President

Engelman Consulting & Training, LLC.

Introduction

Over the years various intellectual tools have evolved to assist companies improve operations and enhance profitability along with customer satisfaction, bringing about a growing emphasis on efficiency and quality as the world economy emerges. Some quality systems include ISO 9000, Quality Operating Systems, Baldrige Quality, Deming System Thinking, Balanced Scorecard, Lean and Six Sigma.[1] Interestingly, the latter two approaches, in combination, are flexible allowing for incorporation of features from the other quality systems as well as supporting them.

While quality management principles have traditionally been applied to manufacturing, service companies have recognized the merits of the Lean and Six Sigma methodologies. They have provided service organizations with a competitive advantage by reducing costs, improving service delivery time and expanding capacity with few or no additions to staff. Examples of general service companies using these concepts include Motorola, General Electric, Bank One, Jefferson Pilot Financial, Community Medical Center Missoula, Montana and Stanford Hospital and Clinic.[2] Examples of PEO, HRO and Staffing Industry companies include Volt Information Sciences, Inc. an IT staffing company and Summit HR.

For small businesses, the challenges associated with providing quality products and services are much greater than for large companies. For instance, a large retailer may offer a wide variety of quality goods at competitive prices, but provide poor customer service. Regardless, customers continue to shop in their stores because of the low prices. In fact, consumers have actually come to expect lower quality from large corporations such as airlines with their lost baggage issues and automobile companies that recall vehicles on a regular basis. For the small business, however, quality products and services are mandatory or your customers will go elsewhere. To be competitive moving forward the PEO/HRO Industry must adapt new tools to prevent this from occurring!![3]

Lean And Six Sigma Concepts

Lean and Six Sigma evolved as independent models for assisting companies improve operations. The genesis of both was the competitive challenge of Japanese manufacturers. Many U.S. companies survived the challenge by adapting their practices. However, in the beginning the ‘shoe was on the other foot.’

Lean

The word ‘Lean’ was not in the business vocabulary when Toyota and other Japanese manufacturers created production system models. In 60’s, still recovering from the war, with only limited resources Japanese companies faced the challenge of U.S. manufacturers with superior technology and resources. With the help of Deming the Japanese created the concept that using less can be better; eliminate waste, focus on quality! Thus focused on waste, quality and the customer, their operational model aimed at using less space, capital, labor, etc. in production system processes.[4] Therefore, anything that was defined as not necessary to create a superior product or deliver a superior service was eliminated!

The term ‘Lean’ relative to products and services first appeared in a 1990 book by James Womack, Daniel Jones and Daniel Roos, The Machine That Changed the World,[5] describing the production system pioneered by Toyota. By then the game had shifted to the Japanese playing field for they now were providing superior products and services, particularly electronics and automotive related, to U.S. and world customers. Consequently, companies in the U.S. began to recognized the value of the ‘Lean tool.’

Language of Lean[6]

As you recognize from the latter discussion Lean, like other disciplines, has a language of its own. Therefore, there are some terms and measurements that are key to understanding its value. Some of these include: Lead Time and Process Speed, Work-In-Process (WIP), Delays/Queue Time, Value-Add and Non-Value-Add, Process Efficiency and Waste.

Lead Time & Process Speed

Lead Time is simply how long it takes to deliver a service or product after a client has placed a request. So what are the drivers of Lead Time? They are embodied in the simple equation created by mathematician John little in 1961[7]:

Lead Time = Amount of Work-in-Progress (WIP)

Average Completion Rate

Basically the equation communicates how long it will take an item of work to be completed (Lead Time) by counting the amount of work waiting to be completed (WIP) and how many ‘things’ can be completed daily, weekly, monthly and so on. Consequently it is possible to reasonably estimate any of the factors in the equation if there are data or a reliable estimate of the other two. For example, if the WIP is known and the completion rate…Lead Time can be estimated. If Lead Time and completion rate are known… the amount of WIP can be estimated.

WIP includes all things in process throughout a company’s operation that need to be completed. It can include customer requests, checks waiting to be processed, phone calls to be returned, reports to be completed, Workers Comp claims needing investigation, providing proposals to prospective customers and so on.

Delays/Queue Time

WIP translates into delays, work waiting to be executed…called ‘in queue’ or in line to be executed. Time waiting in queue is wasted time delaying completion, adding costs to company operations and to clients.

Value-Added/ Non-Value-Added

As process flow/work is tracked, it becomes apparent what activities are adding or not adding value to the company. But, the question is…does the customer see the value and are they willing to pay for it? Thus we have the Value/ Non-Value-added.

Process Efficiency

Process Efficiency is the metric of waste. What percentage of total process time is spent on value added verses waste? The metric used is Process Cycle Efficiency (PCE) relating the amount on value-added time to the total lead-time to process:

Process Cycle Efficiency=Value-added time

Total Lead Time

Interestingly, most company processes are un-lean. Typically they have a PCE of less than 10 percent indicating that most processes have considerable non-value-add waste to be eliminated.[8]

Waste

As noted above waste is anything…time, costs, work adding no value in the eyes of the customer. The amount of waste in process activities is proportional to how long it delays work. The Lean approach shows how to recognize and eliminate waste. There are seven specific forms of waste as originally identified by Taiichi Ohno of Toyota:[9]

1) Over processing--trying to add more value to a product or service than what a customer wants or will pay for.

2) Transportation—unnecessary

movement of materials, products or information.

3) Motion—needless movement of people.

4) Inventory—Any work-in-process that is in excess of what is required to produce for a customer.

5) Waiting Time—Any delay between when one process step/activity ends and the next begins.

6) Defect—Any aspect of the service that does not conform to customer needs.

7) Overproduction—Production of service outputs or products beyond what is needed for immediate use.

With American culture firmly believing more is better, numerous other types of waste have been identified, such as the “seven additional wastes within manufacturing” and the “twelve wastes within warehousing and distribution.” Regardless of these additions, there is widespread agreement throughout industry of an eighth waste.

8) Unused employee creativity – Losing time, ideas, skills, improvements, and learning opportunities by not engaging or listening to your employees. [10]

According to Ohno, overproduction is considered the fundamental waste since it causes most of the other wastes. The American preference for more proves to be counter-intuitive to Lean, with batch processing, large inventories, and the pushing of material to the next process resulting in additional costs and time while reducing flexibility, thus creating waste. [11]

Lean

Ingredients

So what are the key ingredients of lean? Desired quality output and supportive company processes! Defining and documenting processes that create the products or services is key because you cannot identify value stream activities or eliminate waste if they are not known or understood! Therefore, lean focuses on removing waste, non-value-added activities, improving efficiency and cycle time related to processes.[12]

There are five essential steps involved: identifying value, identifying the value stream(s), improving stream flow, working toward perfection, and allowing customer pull. The steps address:[13]

1) Determining what features create value to a product or service from an internal and/or external customer perspective. Value is described in terms of how a specific product satisfies customer needs at a specific place, time and price being evaluated on what features add value, determined by subsequent process output users or the ultimate customers.

2) Of course, the former is directly related to the process activities…those creating and contributing to a positive value stream and those that don’t. What activities contribute to value? All process activities of a company including administrative functions can contribute to a positive or negative value stream and therefore must be evaluated.

3) The key to improved flow is identifying and eliminating negative activities or constraints in processes. Anything that interrupts or slows process flow, uses unnecessary resources or creates recycling contributes to wasted time, money and human resources.

4) The improved flow analysis is a continuous function since there is a tendency for waste to creep into operations. Furthermore, ongoing advances in IT and other fields have the potential for contributing to more efficient and effective value streams.

5) The final key is referred to as ‘customer pull.’ Basically, it means the customer is always the focus therefore company processes must be responsive to providing the desired products and services only when the customer needs them…not before or not after.

Initiating Lean

A 2005 study found the service industries lag in the adoption of quality methodologies where the use is about half of those in the manufacturing, health care and education sectors.[14] The services obstacle with the highest percentage, 58 %, was resistance to change.[15]

To successfully initiate Lean all levels of management must be educated and be committed. Undertaking and maintaining such change in an organization requires a cultural shift. In other words, cultural change involves the introduction of a new vocabulary, building a company wide understanding and changing the way a company thinks and acts in day-to-day operations. [16]

The success factors result from: 1) strong leadership, 2) communicating the need for change, 3) clear and motivating goals and objectives, 4) management of resistance and 5) modifying culture to encourage and maintain change.

Some companies have initiated Lean efforts with a ‘learn as you go’ approach resulting in overwhelmed and confused employees. The best approach is to educate all employees in the concepts and train in the details those who will undertake the first initiative of Lean application to a process. There are quality-consulting companies that can provide assistance until an in house capability exists.

Since processes are being analyzed/evaluated, if company processes have not been documented, this is the next step, starting with a process that has high probability of results. The employees executing the process should be part of the team and thoroughly trained so they understand why they are doing things. They should be part of the improvement process so improvements are sustained. The process is documented at a high level and the value streams identified and mapped. Working with the experts the employees identify waste and the process is reengineered addressing the waste factors. This is executed process by process along with all process interfaces until company processes are Lean. Lean is a continuing endeavor searching for the state of perfection where there is no waste. Service companies that have documented and maintain processes are one step ahead in the game.

Cost

The costs

associated with creating a Lean culture are as varied as the organizations

dedicated to pursuing perfection via the continuous elimination of waste.

Initial costs include awareness education for top management, development of

internal champions and/or the use of an experienced consultant who can

accelerate the learning curve while ensuring processes are in place for

knowledge transfer. Also recommended is the establishment of a Lean office to

help formalize the Lean initiative and provide a center for expertise and

guidance. In conjunction with the rollout, each employee will receive basic

training in the principles of Lean and more specific training when the application

of certain tools is required.

Relatively new are

organizations such as the Shingo Prize for Excellence in Manufacturing, the

Society of Manufacturing Engineers, the Association for Manufacturing

Excellence, and various other organizations, colleges and universities offering

“Lean Certification” programs.[17]

These certifications cost from $4,000 to $14,000 and more, depending on the

program.

To minimize costs

throughout the organization’s Lean transformation, a basic mindset of employing

“creativity before capital” allows for significant improvements by challenging

the human mind. Initially, however, a percentage of employee’s time may be

budgeted to the effort, but eventually the culture will transition to one of

“that’s just how we do business.” The bottom line is Lean will be a

self-funding initiative if embraced by the organization and properly resourced,

with returns-on-investment greater than 10 expected. At this point, benefits

obviously outweigh costs.

Training

Numerous entities provide training ranging from individuals and consulting companies to colleges and universities; some are classroom others on-line. Consequently, becoming knowledgeable and skilled in Lean starts with research. Numerous organizations advertise on the Internet including academia. Check the references.

Six Sigma

Six Sigma addresses analysis of variance focusing on reduction of variation to solve process and business problems using a set of statistical tools. Motorola and General Electric popularized the methodology.[18] Six Sigma is a registered trademark and service mark of Motorola, Inc. dating back to 1986.

Statistical thinking stresses variation exists in all processes and proper approaches can eliminate or minimize it through continuous improvement thus resulting in higher quality. Even processes that run steadily over time are likely to produce unacceptable variation in operation and output due to personnel, equipment, policy changes, etc. Variance reduction to acceptable levels is the objective of Six Sigma.

Language of Six Sigma

The following are just some of the terminology associated with the Six Sigma process.

Six Sigma

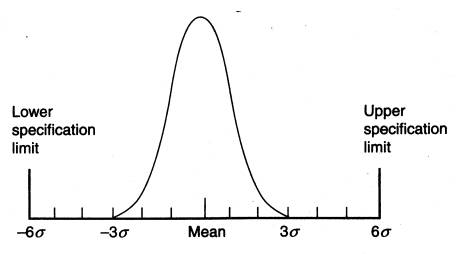

The concept origin is the statistical distribution known as the Normal Bell Shaped Curve with its Mean and Standard Deviations or Sigma shown below. There is positive and negative Sigma, six on each side of the Mean. This distribution shows variability, exactly what the Six Sigma concept attempts to reduce/eliminate, skewing the numbers toward a Plus Six Sigma in favor of the customer.

Michael L. George in his book, Lean Six Sigma For Services, points out, “Six Sigma terminology arises from the relationship between variation in a process or operation and the customer requirements associated with that process. In normal operations the largest concentration of value is around the mean (average), and tails off symmetrically.”[19]

Six Sigma Deviation

Six Sigma numbers represent how the distribution of actual output compares to the range of acceptable values (customer specifications). A defect is any value that falls outside customer specification. The more of the distribution fitting within the specifications the higher the sigma level. The objective is to minimize/eliminate any variation from what the customer expects thus achieving Six Sigma. Consequently, a Six Sigma process will have only 3.4 errors/defects per million transactions/opportunities thus being 99.99966 effective.[20]

Ranjan Sinha provides some examples of the value of operating within a deviation of Six Sigma: [21]

· “A regional postal sorting facility operating at 2.6 sigma (99% effective) might lose 20,000 articles of mail each hour; at Six Sigma (99.99966% effective), only seven articles are lost per hour.

· “In hospitals, a 2.6 sigma level may lead to 5,000 incorrect surgical operations in one week, compared with just two incorrect procedures per week if they operate at Six Sigma.

· “Even more astounding, at 2.6 sigma there are two short or long landings at most major airports daily; operating at Six Sigma, the number of short or long landings is one every five years.”

SIPOC

SIPOC is a chart or diagram that creates a high level map of processes moving from left to right; Supplier, Input requirements, Process, Output, and Customer: Supplier addresses persons, processes, etc. providing what ever is worked on in the process; Input is information or materials provided; Process includes the activities used to produce the product or services; Output includes the products, services provided; and obviously to the final Customer.

Pareto Charts

Pareto charts are bar charts used to represent the relative contribution of each process/activity to the cause of a problem. The number of times an event occurs is represented by the height of each bar creating a histogram. The principle is that 20 percent of something is always responsible for 80 percent of the results.

FMEA

Failure Mode and Effects Analysis is a planning tool that helps anticipate and prevent problems. It includes identifying process activity input, potential failure modes, potential effects and causes along with current controls, responsibility and identifies action teams responsibly.

Champions

Upper management is the Champion. For positive cultural moves to take place to plan for and implement Six Sigma, there must a belief and support for operational change from upper management. Upper management must Champion Six Sigma. Once committed, Champion education/training is provided in its roles and responsibilities to facilitate and manage the Six Sigma process(s) understanding the role of the Belt concept in the process.

Black Belts

Black Belts are change agents. Master Black Belt, manager of change, is the highest level and the technical leader for process improvement, being an expert in organizational operations, as well as having an understanding of the statistical methodology and the mathematical theory on which Six Sigma is based. Devoted 100 percent.

A Black Belt is the ‘in the trenches’ technical leader actively involved in the change projects with oversight of the extraction of information about operations, identifying problems and assisting in the change process. They are process oriented, having basic mathematical and some advanced statistical skills. Devoted 100 percent.

Both Belts receive four to eight weeks of professional training and are experienced in the DMAIC discussed below.

Green Belts

Green Belts are typically supervisors, engineers, or quality control experts participating in projects without leaving their other responsibilities. They receive half as much formal training as Black Belts and rely on Black Belts for mentoring. Green and Belts lead projects, work on problems in their area of responsibility.

Six Sigma Ingredients

Six Sigma is a rigorous research approach with the objective of reducing process variation that includes five steps: Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve and Control referred to as DMAIC: [22]

1) Define-involves the project team completing a detailed analysis of what is to be accomplished and confirmation with management agreeing on such things as the problem being addressed, customers affected and their input and outputs, how the current process(s) fail to meet needs, link to corporate strategy, project boundaries, project goal, what indicators or metrics will be used to evaluate success, etc. Relative to boundaries, when processes have been documented it’s simply a matter of identifying those that are to be included in the research, but if they have not been documented identifying value streams to be analyzed is difficult requiring the team or others to document processes of interest.

2) Measures-addresses evaluating process operations and outputs to determine the causes of unacceptable products and services. Key process characteristics are categorized, measurement systems are identified, verified and data collected.

3) Analyze-basically once data are collected it is analyzed converting the raw data into information providing insight into process activities and there operation. Identified are the fundamental and most key causes of unsatisfactory products or services; the causes of variation.

4) Improve-treats finding solutions to process problems and making modifications. The results are measured comparing the new against the old process outputs. Then it can be determined whether the changes were beneficial or if additional changes are required.

5) Control-when a process is performing as desired with predictable outputs, methods must be put into place to maintain control of the operation and they must be thoroughly documented. Then the process is monitored to assure the process is operating within acceptable limits. This is normally the job of the designated process owner.

Initiating Six Sigma

As was mentioned above putting Six Sigma into play in an organization is a team effort, starting at the top. It takes time to put all the team members in place because of the

education and training required. Projects should be carefully selected by the organizational leaders to ensure a positive impact on customers, shareholders and/or employees. Also the leaders must carefully select those who are to be trained ensuring capable, committed individuals are in place. Further each team member must know the role of all the players and to whom they depend on and for what. Once the team is ready the DMAIC process is executed gathering data, conducting statistical analysis and designing and conducting process design experiments to identify and reduce variation to acceptable limits.

Overtime, companies dedicated to the concept, create a cadre of Champions and Belts working on designated problem areas. The speed of the transition is enhanced as the culture changes and it becomes a tool to improve all processes. Once in place it is one key ingredient in the continuing evolution of a company in the challenging global economy.

There are several reasons why the implementation of the tool will not be successful some which have been alluded to previously. Most common reasons are lack of guidelines for establishing/leading the program along with management support.[23] Typically companies with a rigid hierarchical organizational structure, resistant to change, placing blame on individuals for the way things are done, managers not thinking highly of their staff, an unwillingness to provide adequate funding will fail![24]

Cost

What are the costs associated with creating a Six Sigma program? A program requires planning, time, personnel, training, consultants and others. Fielding a team of Champion and Belts is expensive. Introductory team training may be in the $10,000-$20,000 range with total per Black Belt training typically costing around $25,000.[25] But, remember all employees must be brought up to speed to be supportive of the effort; it’s a cultural change from top to bottom, adding to the cost.

On a positive note the rewards can be considerable. A typical Six Sigma project, depending on the size of the company and project undertaken, is estimated to add in the neighborhood of $175k-$250k to the bottom line.[26]

Training

Similar to Lean training previously mentioned, numerous entities provide training ranging from individuals and consulting companies to colleges and universities; some are classroom others on-line. Consequently, becoming knowledgeable and skilled in Six Sigma starts with research. Numerous organizations advertise on the Internet including academia. Check the references.

A final point, there are no Six Sigma standards or certification per se.[27] Certifications are provided by individual training facilities and not by a national or international entity with such responsibility.[28]

The Lean Six Sigma Team

Many companies believe they must choose one approach to the exclusion of the other rather than creating an environment where each is available and put into play as circumstances dictate. A firm belief that all processes, to varying extents, include non-value-adding waste as well as variation, confirms the value of integrating and applying the Lean and Six Sigma tools best suited for addressing the problem.

For example, when an improvement opportunity arises, the Champions and Black Belt would conduct a measurement review and discuss approaches, available tools, etc. If it is determined waste reduction is the initial need, a Lean Team implements the analysis addressing the seven primary causes of waste. If a determination is made the process has considerable variance contributing to output problems, a Six Sigma Team will be called upon to conduct its research and analysis in conjunction with the Lean Team efforts, using statistical methods to identify and decrease or eliminate process variation.

Since Lean and Six Sigma tend to require different skill sets of employees, especially considering the highly mathematical and technical tools in the Six Sigma toolbox, caution must be exercised to avoid competing efforts. By treating Lean and Six Sigma as two tool kits and setting up a situation in which different groups go to war over whose tool kit is bigger and better, the company creates a self-defeating improvement program. What companies need to remember is that both are extremely powerful toolkits, but in the end they are just tools.[29] True success will be realized when management philosophy drives the application of the right method at the right time.

It is also important to remember these teams are not working independent of the process owner and process workers. They work together to identify and solve process problems whether human error, policy, equipment, process, materials, organizational, etc. based.

Concluding Remarks

After deciding which path to travel, Lean, Six Sigma, or Lean Six Sigma, and completing the requisite training to initiate enthusiasm and action, there are six “must do’s” for managers responsible for ensuring employee and organizational success. They are:[30]

1. Pick the right projects

2. Pick the right people

3. Follow the method(s)

4. Clearly define role and responsibilities

5. Communicate, communicate, communicate

6. Support ongoing education and training

Entering this quality arena is a major undertaking to say the least. Major commitments and investments are required. But these methodologies have been proven to work for manufacturing and service businesses in the United States as well as around the world. Nevertheless, for any business, large or small, the concepts can be overwhelming, let alone the dollar and human investment. So what’s a small company with limited resources to do? Take one step at a time. Learn, educate and apply what’s practical and cost-effective:

1) Become educated about Lean and Six Sigma concepts through books and magazine/journal such Quality Progress and Quality Management Journal.

2) Join the American Society for Quality as well as their local organizations or others to talk directly with people affiliated with companies using these tools.

3) With consultation, commit the company to the quality concept and educate management and staff with in house presentations and discussion groups.

4) With consultation, document company processes to begin to thoroughly understand operations, while having a person or persons trained in Lean methodology.

5) With consultation, using the Lean methodology, conduct a process analysis identifying waste and restructure processes.

6) Moving to Six Sigma requires consultation and the hiring or selection of a internal qualified staff member to be trained in the related disciplines.

The priority for small

businesses is to become knowledgeable and being prepared to integrate the

methodologies and tools when practical and cost-effective. Like other improvement initiatives, this will

become a multi-year transformation of people, processes, and culture. Is there

a secret to ensuring long-term success while realizing significant

improvements? Yes, as management at all levels of the organization embrace the

cultural change with a passion.